By: Jeremy Loudenback

Jeffrey Thomas has always used basketball as an outlet when times get tough. But nowadays when the 23-year-old Southern Californian needs to take a breather, the natural extrovert can’t meet up with his friends or family. Anything resembling a real game of hoops is forbidden in the age of social distancing, so he finds himself shooting baskets by himself, in an empty church parking lot behind his apartment complex.

Until the pandemic hit, Thomas, a former foster youth, wasn’t quite as stressed out. At least he had his job at an H&M clothing store, within walking distance of his two-bedroom apartment in Pasadena.

But in mid-March as the pandemic began to intensify, he got the phone call that confirmed his fear: He was getting laid off. And Thomas was far from alone. Seventeen of the 18 young residents at the Hillsides temporary housing complex where he lives had also lost their jobs. Nine weeks into the pandemic, California’s unemployment rate has risen to a record-high 15.5%, which includes the largest monthly job loss on record.

Recent data confirm that joblessness among youth at the Hillsides program is just one of many signs that the unemployment tsunami tearing through the country will batter former foster youth more intensely than other groups of work-eligible adults.

Two surveys released in May – one by the national foster youth advocacy group FosterClub, and the other by iFoster, a California-based nonprofit – show just how bleak life looks for young people who’ve grown up in foster care: An overwhelming majority have lost jobs during the pandemic. Still others have had difficulty accessing entitlement benefits to meet basic needs, struggling to receive unemployment checks and food stamps.

FosterClub’s survey of 600 people found that 65% of former foster youth between the ages of 18 and 24 are unemployed as a result of the pandemic, with half of those unable to receive unemployment insurance.

iFoster surveyed about 300 young Californians who’ve spent time in the system, asking about their experiences during the pandemic. Thirty percent of the youth ages 15 to 26 are newly unemployed, even though many of them weren’t working or going to school at the time of the pandemic. Nearly every employed young person who was surveyed had either been laid off or has seen a decrease in hours. Some had to decide whether to keep their job and continue living in a group home or shared temporary housing because of fears of infection, according to iFoster staff.

Forty-seven percent of those surveyed by iFoster reported that they were having difficulty getting enough food to eat or could not afford to buy the food they needed, and 37% had concerns about their housing stability.

Even during economic boom times, many former foster youth find it hard to land a job after leaving care. Now advocates are even more worried as the young people confront an unprecedented economic crisis at this precarious point in their lives.

“We shouldn’t be letting them fall off the cliff, which is what we’ve been doing,” said Serita Cox, executive director of iFoster, a California nonprofit that provides job training, technology and other support to TAY. “But all of a sudden, that cliff has gone from 20 feet to 200 feet.”

Since being laid off from the clothing store two months ago, Thomas has had to re-evaluate his plans.

“It was tough,” Thomas said of his layoff, with a frankness that revealed his courage despite the stress he is now under. “I like working, I like having money in my pocket.”

So he is not waiting around. Now, with the help of a tutor, he has focused his efforts on studying for an exam he’ll need to pass to join the Marines, a lifelong dream. Hillsides, a Los Angeles-based agency serving 17,000 children and families at more than 40 sites in the region, has provided Thomas and his housing program cohort $50 each in weekly grocery money, plus it has helped cover the rent and utilities for some during the pandemic.

Dennys Valle, an on-site manager at Hillsides’s temporary housing program in Pasadena, does grocery shopping for the youth in the program every Friday. Thanks to philanthropic support, the nonprofit has provided every young person with an additional weekly $50 grocery tab during the pandemic. Photo courtesy of Hillsides.

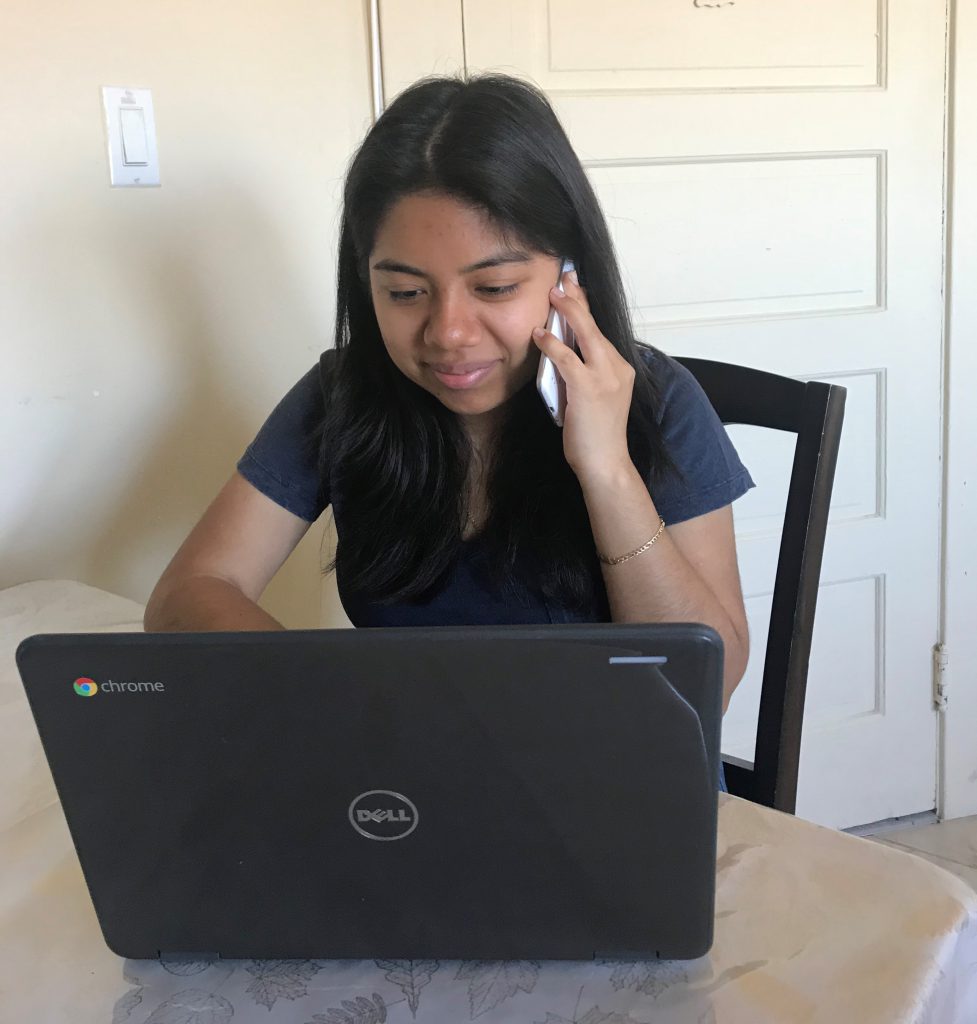

The iFoster survey that captured the experiences of foster youth like Thomas is part of a unique effort to reach foster youth during the pandemic. Last year, the organization orchestrated a $22 million public-private partnership to offer free smartphones to young people from the foster care system, ages 13 to 26. As the pandemic battered the country, the group distributed more than 6,000 mobile phones to Californians and almost 400 to New York City residents. iFoster sent out its 10-question survey to 2,800 recent recipients of the phones in California during the pandemic.

iFoster Executive Director Cox said young people have been using the phones to stay in contact with family members, keep up on schoolwork and even maintain tele-health appointments during the pandemic. Her organization has also received state funding to distribute more than 3,300 laptops, and is expanding distribution of cell phones to foster children between the ages of 5 and 12.

Such communication can be a lifeline for groups tracking needy populations.

iFoster followed up with survey respondents to help them address needs they had identified, such as finding food banks near homes. In June, Cox will provide online training to help young adults find work, including a virtual job fair and tips about applying to jobs online.

More than three-fourths of the former foster youth over 18 who responded to the survey are currently looking for work during the pandemic. And more than half said they are willing to risk taking jobs that could expose them to infected people.

Even during more flush times, finding and keeping a job was an extraordinary challenge for many young adults exiting the foster care system. According to a 2018 study from researchers at the University of Chicago’s Chapin Hall, just 57% of foster youth were employed at age 21, and compared with their peers in the general population, they were far less likely to have ever had a job they kept longer than nine weeks.

As the recession deepens, Cox said she is most worried about how these youth will fare when competing with so many others with far greater work experience and qualifications. More than 38 million Americans have filed for unemployment since the start of the pandemic in March. Some economists suggest that the actual unemployment rate — including workers who have given up looking for work — may have even pushed past the peak of the Great Depression.

“Our kids are going to be massively challenged,” Cox said. “They’re going to be at the bottom of the list for hiring. Like any recession, who are the last to be hired back? The youngest and the oldest.”